Interview: ‘On Deep Fakes & Transparency’, Creative Review

The Role of Art in Understanding Complex Changes in Politics & Tech

Really pleased to see an extended version of an online interview I had with Creative Review in June now in print form for the latest August / September issue. Unfortunately access to the online article is behind a paywall so I’ve included the text below with some images to break up the flow.

Bill Posters On Deep Fakes & Transparency

Artist-researcher Bill Posters talks to CR about creating viral celebrity deepfakes, as well as the role of art in making complex topics relatable and the motivations behind Spectre, his new award-winning installation with Daniel Howe.

Famous people will say anything these days. Mark Zuckerberg admitting to abusing Facebook users’ information, or Kim Kardashian chatting about manipulating public data for money is a little unexpected though.

Look as closely as you want, but it’s nigh on impossible to tell that these clips are fakes, if it weren’t for the purposefully jarring content of what they’re saying. The series – which also counts Morgan Freeman and Marina Abramović among its ‘stars’ – is part of a broader effort from transatlantic duo Bill Posters and Daniel Howe to lay bare the dubious technological underbelly of modern society.

The artist-researchers wanted to get across their message on the obscurity of truth and lack of transparency in the digital age. Their approach was two-pronged: an immersive installation, propped up by a series of ‘deepfakes’ made in collaboration with Canny AI. A deepfake is a layman’s term for a generative AI video – a disconcertingly believable dub, which typically requires a “synthesised image and synthesised audio. Then the two are generally combined,” Bill Posters tells CR.

The realistic outcome is achieved thanks to neural networks – systems modelled after the human brain. The specific kind of neural networks used for deepfakes are called GANs (generative adversarial networks, if you were wondering). A short source clip is fed to the AI to train it, and then two GANs essentially battle back and forth with one another, constantly comparing themselves to the original clip. By battling it out, the GANs are able to “create a better output” – in other words, a more accurate video.

To achieve the doctored vocal content, an actor will record the new audio while video footage of them is fed into a machine learning system that tracks their mouth movements, which are then merged with the original clip. “Ninety per-cent of the video is similar to the source clip. It’s just the bottom region of the face – below the nose to the chin-line and the cheeks – that’s actually the synthesised component,” says Posters. While voice synthesisation is more complicated and can take up to a week, he explains that image synthesisation can be done in matter of hours, not days.

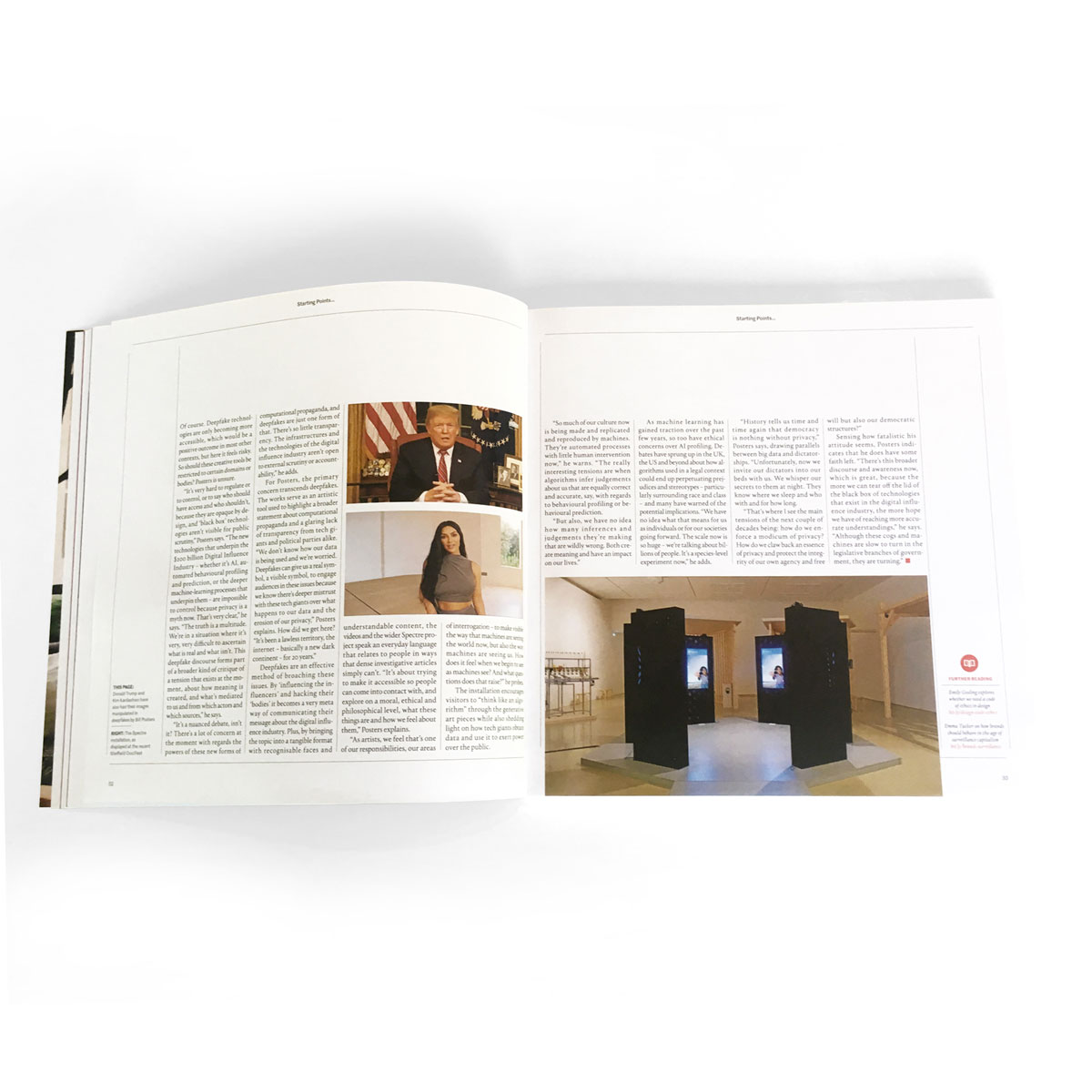

These celebrity deepfakes recently went viral, grabbing headlines on major news and press outlets and sparking debate. Amidst the media flurry, though, a deeper conversation was brewing about the unforeseen influence that technology has on truth, transparency and surveillance capitalism – central themes in the duo’s new installation. Spectre was unveiled earlier this month at Sheffield Doc/Fest after winning this year’s Alternate Realities commission – with support from Arts Council England, British Council, Site Gallery and MUTEK. The installation is set to travel to MUTEK in Canada and, fittingly, to the USA for the 2020 elections.

The visual design of the installation was inspired by iconic monolithic structures and sculptural art, taking influence from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, conceptual artists such as Robert Morris and even Stonehenge – all symbolic of breaking new frontiers in their own right. The installation itself draws upon visitors’ data to create an immersive experience curated by algorithms that cleverly illustrates how public information is lost into the ether and used in ways many are unaware of. As a result, Spectre interrogates forms of computational propaganda including OCEAN (Psychometric) profiling; generative image and text; ‘deep fake’ technologies; and micro-targeted advertising via a ‘dark ad’ generator. Posters says that Spectre weaponises many of the same technologies employed by Silicon Valley giants, ad companies and political campaigners alike to influence our behaviours – both online and in the voting booth.

“The Spectre project emerged from trying to really understand what these new forms of computational propagandas are – like the ones that have been revealed by investigative journalists: Carole Cadwalldr at the Guardian, and such,” Posters explains, referring to the findings related to the Vote Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum. “We just set out to interrogate them and understand what these things are, how powerful they are. We wanted to give abstract concepts like Dataism and surveillance capitalism a tangible, material form, to explore these logics using an immersive installation so we can engage people in the power around these new kinds of technologies and the power of the digital influence industry more broadly.”

The project comes at a time where Leave campaigners are still evading police investigation following the EU referendum vote (“Brexit was nearly three years ago, right? And still there’s no real solid transparency or regulation on these types of tech,” says Posters), and the Trump administration is continuing to take advantage of dubious technologies for its own political gains. From the Cambridge Analytica data scandal that many argue influenced the 2016 elections, to the altered footage that Trump shared a few weeks ago of House Speaker and Democrat Nancy Pelosi, these tactics only seem to be gaining momentum.

Online policies around deepfakes and altered imagery are muddy. Facebook and Instagram branded the Zuckerberg deepfakes as “misinformation” even though they have been declared artworks and as a result are the world’s first contemporary art ‘deepfakes’. On the flip side, Facebook wouldn’t remove the altered video of Pelosi, even though it clearly has more obvious political repercussions than the deepfakes by Posters and Howe. Elsewhere, YouTube took down the Pelosi clip along with the duo’s Kim Kardashian deepfake under the guise of a copyright claim by Condé Nast. It seems nobody knows where to draw the line.

Should we be concerned about deepfakes and their potential repercussions, particularly in such a tumultuous political and social climate? Of course. Deepfake technologies are only becoming ever more accessible, which would be a positive outcome in most other contexts, but here it feels risky. So should these creative tools be restricted to certain domains or bodies? Posters is unsure.

“It’s very hard to regulate or to control, or to say who should have access and who shouldn’t,because they are opaque by design and ‘black box’ technologies aren’t visible for public scrutiny” Posters says. “The new technologies that underpin the $200 billion Digital Influence Industry – whether it’s AI, automated behavioural profiling and prediction or the deeper machine learning processes that underpin them – are impossible to control because privacy is a myth now. That’s very clear,” he says. “The truth is a multitude. We’re in a situation where it’s very, very difficult to ascertain what is real and what isn’t. This deepfake discourse forms part of a broader kind of critique of a tension that exists at the moment, about how meaning is created and what’s mediated to us and from which actors and which sources.”

“It’s a nuanced debate, isn’t it? There’s a lot of concern at the moment with regards the powers of these new forms of computational propaganda, and deepfakes are just one form of that. There’s so little transparency. The infrastructures and the technologies of the digital influence industry aren’t open to external scrutiny or accountability. In fact a recent report from the UK’s Information Commissioners Office in June has found that the Ad tech industry is operating illegally in relation to GDPR laws which is huge” he adds.

For Posters, the primary concern transcends deepfakes. The works serve as an artistic tool used to highlight a broader concern about computational propaganda and a glaring lack of transparency from tech giants and political parties alike. “We don’t know how our data is being used and we’re worried. Deepfakes can really give us a real symbol, a visible symbol, to engage audiences in these issues because we know there’s deeper mistrust with these tech giants over what happens to our data and the erosion of our privacy,” Posters explains. How did we get here? “It’s been a lawless territory, the internet – basically a new ‘dark continent’ – for 20 years.”

Deepfakes are an effective method of broaching these issues. By “influencing the influencers and hacking their ‘bodies’ it becomes a very meta way of communicating their message about the digital influence industry. Plus, by bringing the topic into a tangible format with recognisable faces and understandable content, the videos and the wider Spectre project speak an everyday language that relates to people in ways that dense investigative articles simply can’t. “It’s about trying to make it accessible so people can come into contact with and explore on a moral, ethical and philosophical level what these things are and how we feel about them” Posters explains.

“As artists, we feel that’s one of our responsibilities really, our areas of interrogation: to reveal or make visible the way that machines are seeing the world now, but also the way machines are seeing us. How does it feel when we begin to see as machines see? And what questions does that raise?” he probes. The installation encourages visitors to “think like an algorithm” through the generative art pieces, while also shedding light on how tech giants obtain data and use it to exert power over the public.

“So much of our culture now is being made and replicated and reproduced by machines. They’re automated processes with little human intervention now,” he warns. “The really interesting tensions are when algorithms infer judgement about us that are equally correct and accurate, say with regards to behavioural profiling or behavioural prediction, but also we have no idea how many inferences and judgements that they’re making that are wildly wrong. Both create meaning and have an impact on our lives.”

As machine learning has gained traction over the last few years, so too have ethical concerns over AI profiling. Debates have sprung up in the UK, the US and beyond about how algorithms used in a legal context could end up perpetuating prejudices and stereotypes – particularly surrounding race and class – and many have warned of the potential implications. “We literally have no idea what that means for us as individuals or for our societies going forward. The scale now is so huge – we’re talking about billions of people. It’s a species-level experiment now,” he adds.

“History tells us time and time again that democracy’s nothing without privacy,” Posters says, drawing parallels between big data and dictatorships. “Unfortunately, now we invite our dictators into our beds with us. We whisper our secrets to them at night. They know where we sleep and who with and for how long.”

“That’s where I see the main tensions of the next couple of decades being: how do we enforce a modicum of privacy? How do we claw back an essence of privacy and as a result protect the integrity our own agency and freewill, but also our democratic structures as well?”

Sensing how fatalistic his attitude seems, Posters indicates that he does have some faith left. “There’s this broader discourse and awareness now, which is great, because the more we can tear off the lid of the black box of technologies that exist in the digital influence industry, the more hope we have of reaching more accurate understandings,” he says. “Although these cogs and machines are slow to turn in the legislative branches of government, they are turning.”

Words by Megan Williams & Bill Posters.

You can pick up a copy of Creative Review for £12 here.